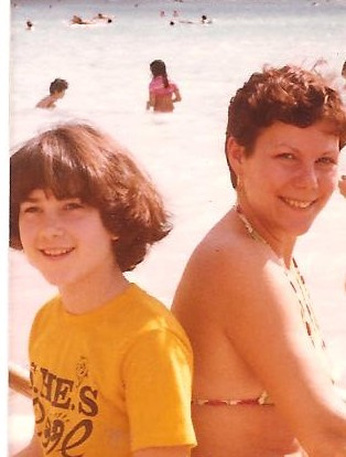

The warble sounded on the police radio to indicate a serious incident -- attempt suicide. I listened to the call that was happening in a different part of the city that I worked. “The witness is saying that this woman is yelling that she wants to die,” said the dispatcher. “She is described as a white female, 54 years of age, approximately 5’4” and 120 pounds, bleached blonde hair and goes by the name of Corley.” I turned off my police radio. Corley was known to police – impaired driving, assaults, mental health, public disturbances – and I knew her too. But I knew her by another name. I knew her as mom. I didn’t always ignore my mom’s pleas for help. In the early 1970’s, it was a normal childhood with hard-working parents. Didn’t every nine-year-old get dropped off at Safeway with a blank cheque? Things changed when I got to high school in the 1980’s. My mom split her time between launching the first indoor tanning salon and sleeping on the family room couch – unshowered and in that damn purple housecoat -- for months at a time. I didn’t bring friends home. If we talked, we fought. But I didn’t understand depression then. I don’t remember “I Love You’s”. I don’t remember hugs. But I also didn’t hear “be careful” or “you can’t do that” which allowed for fearless exploration. “Hey mom, can I teach myself how to drive a standard in your courtesy car?” “Sure,” she said. “Hey mom, Deb and I are going to Puerto Vallarta for spring break.” I said. “Ok,” she said. Things got normal again while I was at university in the early 1990’s, and we became roommates in a downtown 2-bedroom apartment. I saw prescription bottles but didn’t know why she was taking medications. She taught me how to run and joined me in my first 10K race. She introduced me to a vegan diet. We road tripped in her Volkswagen convertible and watched the stars in Utah’s Red Rock Canyon at midnight. I loved how she overruled David Lee Roth’s ‘I-I-I-I Ain’t Got No-bo-dy” and sang “I-I-I-I Got Some-bo-dy”. After I graduated, we became partners in a health and fitness business and I started to see mood fluctuations. I couldn’t keep up with her disjointed, racing thoughts and after two years, I moved out and left the business. But not before she racked up $10,000 in company bills that I later paid personally. Then she started to drink. I didn’t understand what was going on but I tried to help. I picked her up at the police station. At every hospital emergency room. I loaned her money. I cleaned vomit from her bathtub. But after five years, my help wasn’t helping. So I distanced myself – maybe too much. I was sad when she lost her apartment, her business, her beloved sailboat. But I kept saying no. Even when an emergency room nurse said, “what kind of daughter are you, you won't pick up your mom?” The worst kind I guess, but I don’t know what else to do. In 1998, I decided to become a police officer. “Michelle, you’ll make a great cop,” she said but I created more distance. “Mom, if you get in trouble with police, don’t you dare tell anybody who I am,” I said. She promised. And she did become known to police. Our uncommon surname had many officers asking if I knew her. “That Corley is nuts, are you actually related to her?” asked one officer. I said no. In October 2004, I accepted an invitation to work a temporary position in Car 87, a partnership program between Vancouver Police and Vancouver Coastal Health Authority. I almost didn’t take it. I wanted drug squad. But I was ready for a change and said yes. A three month assignment turned into four years. My partners were psychiatric nurses and we responded to mental health incidents throughout the city. Crystal meth-induced hallucinations. Suicides. Self-harm due to alcohol. Schizophrenia. Delusional behaviour. And, bi-polar disorder. I spoke to hundreds of people with bi-polar disorder. I spoke to their families. I had meetings with mental health workers. I interviewed psychiatrists. And I started to understand. But for the next few years, I still drove by when I saw her on the streets. Once, I saw her causing a scene at our station’s public information counter, I ducked into a back stairwell. In the last year of my assignment, we spoke with a woman who was on the verge of a crisis. When we asked about family supports she opened a drawer and pulled out a photo of a uniformed RCMP officer. “I have a son. I’m very proud of him but he’s told me not to tell you about him.” The next time I saw her on the corner of Main Street and Gore, I stopped. “Hi Michelle!” she said as she ran across the street to my police car. I knew my partner would wonder why I ignored safety and chatted to a person on the street through an open window. “Who was that?” he asked after I drove away. “That was my mom”. After that, whenever I saw my mom, I stopped and we'd chat. But I learned how to keep boundaries. “Okay, you can come over to my house, but you can only stay one hour and I won’t let you in with that wine bottle.” “Oh, you are a good cop,” she said and we’d both laugh. My mom no longer asked for money. She no longer asked for favors. She was always smiling. She had friends all over the Downtown Eastside. She still drank but, “the drinking binges get shorter and shorter and the sober times get longer and longer,” she said. My mom’s medications helped stabilize her moods. She started sailing again. I was proud of her when she was part of a 6-person crew to Hawaii. In 2005, I told her I wanted to leave policing and start a dog training business. “You’re brilliant, go for it,” she said. The next time I saw her she gave me a dog training book that she bought at a garage sale for a dollar. I still have that book. And later in the fall, I met my mom at 7th and Alberta Street. It was sunny. We sat on a park bench and watched dogs play. I told her about my boyfriend and asked why she never had a steady one after her divorce. “I’d love to be in a relationship, but I love my independence too. I want him to have his own sailboat, so we can sail side by side, together,” she said. Having joked to friends about wanting a husband who lived in his own apartment down the hall, I finally felt it. I was my mother’s daughter. On January 4, 2006, I resigned from the Vancouver Police Department. Twenty-two days later she was killed in a road accident. She was 58. Being the ever optimist, I almost heard her say, “but hey, I was cycling in Mazatlan, what better way to go!” I am now forty-three. I still eat a vegetarian diet and have a positive body image. I believe I can do anything (mostly). I am glass half-full girl. I love adventurous travel and Stanley Park is still my favorite place to run. And I strongly believe that behind every person is a story worth knowing. ----- For information on mental health, please see the Canadian Mental Health Association ------ Thank you for spending your precious time with my story. If it resonated with you, let me know at [email protected] ... I love getting surprise emails. Comments are closed.

|